Classical culture and knowledge of history were once the prerogative of a perfect gentleman. Jean Warin, engraver of the French kings, introduced the young Louis XIV to the beauty of numismatics and the collection of prestigious coins.

Today, monarchs have given way to collectors, humanists and art lovers, but coins still retain their enchanting charm and mystery. They reveal ancient beliefs and offer a rich and varied iconography. Connoisseurs will be seduced by the variety of portraits of illustrious men and women, and representations of divinities, animals and monuments.

By collecting and studying coins, numismatics enthusiasts pass on and preserve the heritage of the great personalities who shaped our world. Assembling a coin collection is beginning a journey through time, an artistic and historical exploration immortalised by the masters of the past.

The first coins were issued in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) around 650 BC, in the form of globules of electrum (a mixture of silver and gold). The last king of Lydia, Croesus (c. 560-546 BC), was the first to separate the two metals and to strike silver and gold coins.

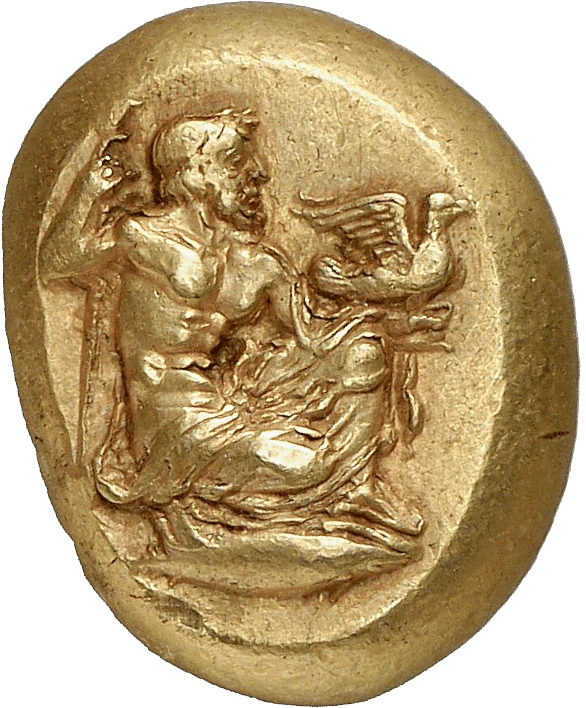

The best period in the coinage of the Greek cities was between 500 and 350 BC, when the artists created the most beautiful coins ever, so beautiful that some Roman emperors, a few hundred years later, began to collect them.

Most Greek coins depict divinities, heroes or animals, symbols of the cities (the owl for Athens, the crab for Akragas, etc.).

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (336-323 BC), the use of Greek coins spread from North Africa to India, and while the conqueror did not issue coin with his portrait, his successors did not hesitate to do so. Alexander’s generals created dynasties. Some of these rulers are known only by their coins.

The first coins to circulate in the Celtic world were those of Philip II of Macedonia (359-336 BC) and his successors. The early Celtic engravers imitated them, before creating complex motifs, including geometric shapes, interlacing and spirals. These patterns, inspired by nature and Celtic mythology, reflect a refined aesthetic sense and a rich cultural tradition. Through coins, Celtic art was rediscovered in the mid-twentieth century and had a profound influence on modern art, particularly on painting.

Picasso, in his Cubist works, also used powerful symbols and oversimplified forms to express complex ideas, depicting human figures or metamorphosed objects. It is interesting to draw parallels between the works of great artists like him and Celtic art, particularly in the representation of complex images in a reduced space and the transformation of conventional forms to explore new artistic perspectives.

Roman coins date back to the very beginning of the 3rd century BC. Initially strongly influenced by Greek coinage, they deeply evolved in 211 BC with the creation of the silver denarius, which had a profound influence on Western monetary history for centuries. During the Republic, the motifs depicted were mainly related to mythology and significant events, such as the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar.

From the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), coinage became imperial. Before the advent of modern media, coins were an essential vector of information, circulating throughout the empire and even well beyond its borders, as shown by the many Roman coins found in India.

As a propaganda tool, coins were used to publicise the emperor’s victories and achievements (major construction projects, organisation of circus games and chariot races, distribution of wheat). The emperor frequently associated members of his family on his coinage to consolidate his dynasty. This immense gallery of portraits also reveals a whole world of elaborate hairstyles and feminine fashions.

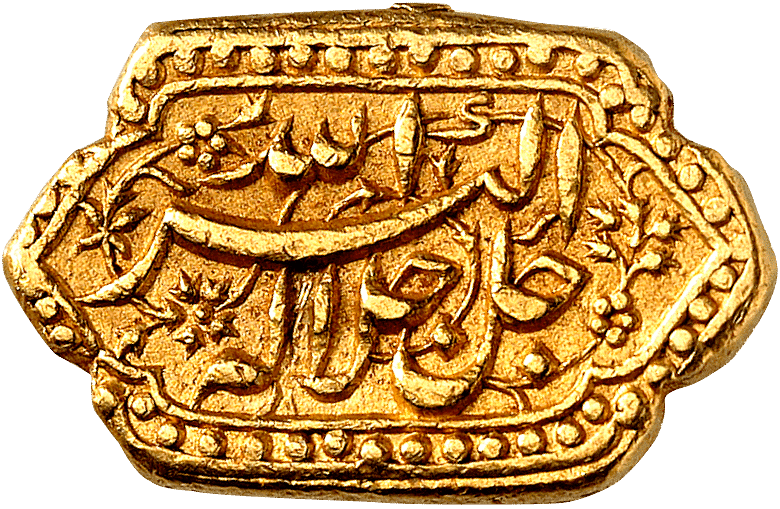

Born in the first century of the Hegira, Islamic coins are renowned for their remarkable use of calligraphy, their stability of weight and their exceptional quality, which made them the preferred commercial tool of merchants from Central Asia to the Atlantic Ocean.

They reflect not only the cultural and religious values of Islam, but also the importance attached to the aesthetics and beauty of inscriptions. This practice influenced the ornamentation in the West, introducing the art of arabesques and complex compositions into architecture and decoration. This movement reached its peak with the Orientalists of the 19th century.

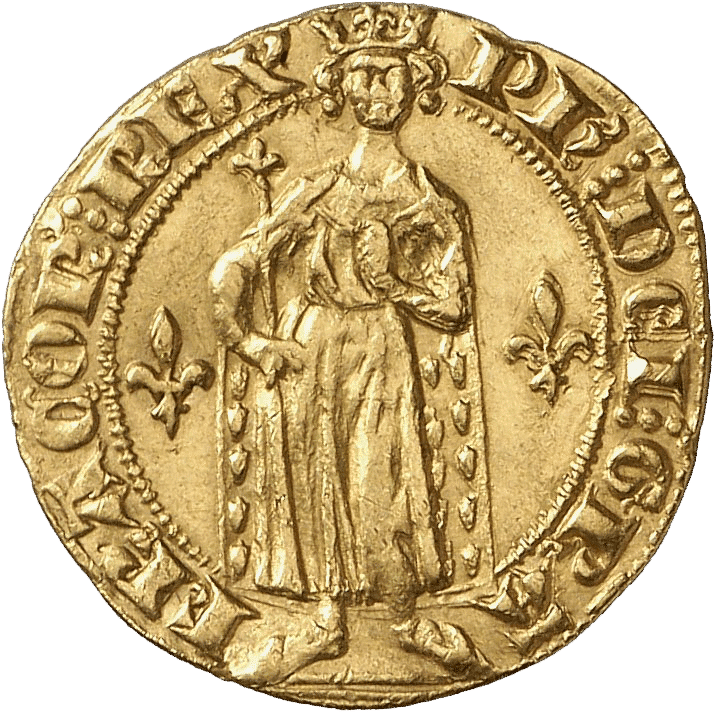

The Middle Ages began with the fall of the Roman Empire (476 AD), accompanied by economic decline and a shortage of precious metals. The emperor Charlemagne (800-814 AD) carried out a deep reform of the monetary system and created a high-quality silver denarius that influenced European coinage well beyond the borders of the Carolingian Empire.

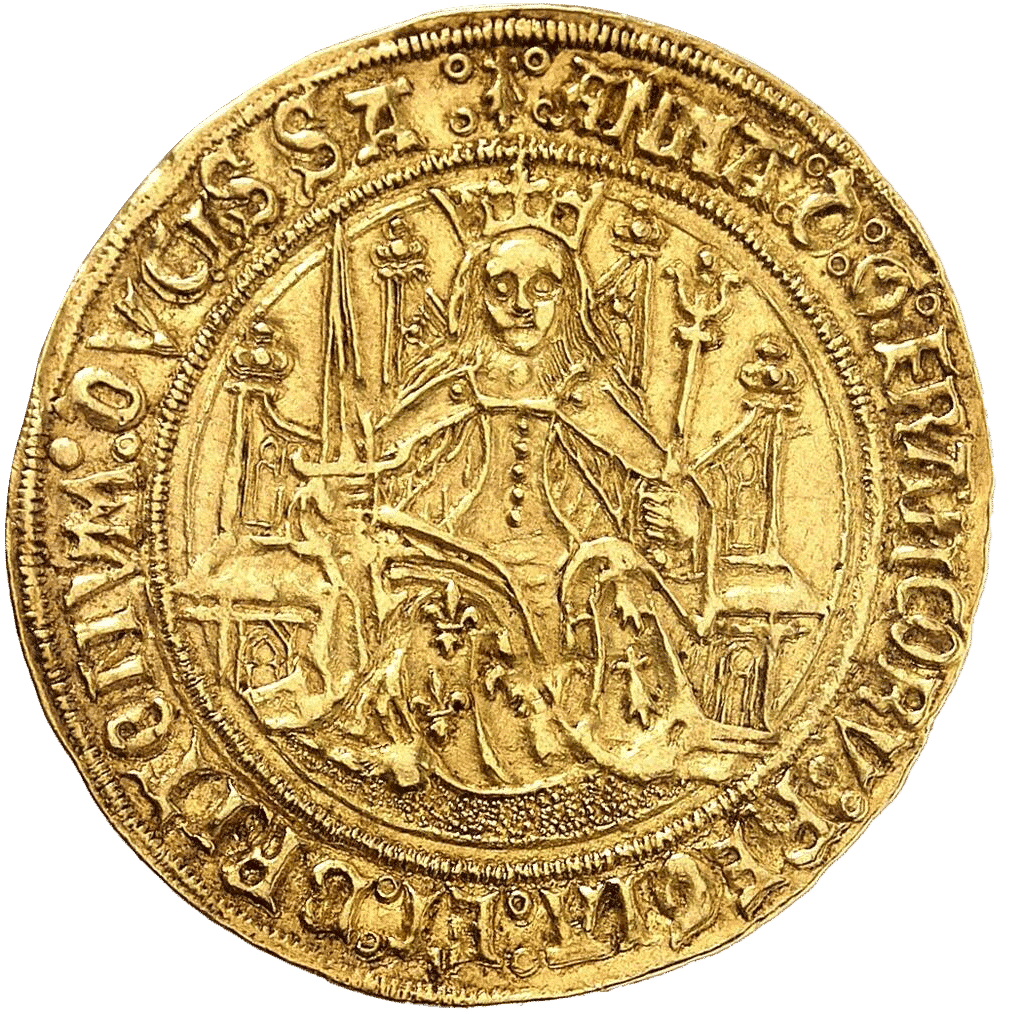

However, it was not until the thirteenth century and the considerable expansion of trade in the Mediterranean that gold coins and larger silver coins reappeared. The first to resume the use of gold were the wealthy merchant cities of Italy (Florence, Venice and Genoa), soon followed by France and the rest of Europe. European monarchs began issuing increasingly prestigious coins, reminiscent of the greatest Gothic masterpieces of the period.

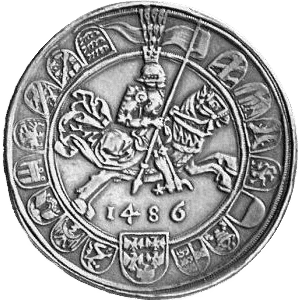

During the 15th century, Europe underwent major philosophical, political and monetary reforms. A return to the ‘cult of beauty’ was evident in all areas of art, including the design of coins. The first large silver coin, the taler, was issued in Austria in 1486.

The taler had a considerable influence on coinage throughout Europe. It became also a model for coinage in other parts of the world. The taler was the basis for many coins of the 17th and 18th centuries, including the English crown, the Norwegian daler, the Russian rouble, the Dutch ducat and the American dollar.

The discovery of the New World in 1492 also led to an influx of precious metals into Europe, allowing the various monarchs and princes of the Renaissance to indulge their taste for luxury and prestige. This trend was also reflected in the increasingly frequent practice of striking medals as gifts for high dignitaries and distinguished guests.

The size of the new coins allowed the artist to use a larger surface area and, as a result, to pay greater attention to detail. Dürer, Benvenuto Cellini and Pisanello were among the famous artists who engraved dies.

Gradually, the coinage became national, although many towns and regions retained their independence in this area. This was particularly the case in Switzerland, where each canton issued its own coinage until 1850, when the first federal coins were issued.

The use of paper money began to spread gradually across Europe in the 17th century, providing a new medium for the iconography of a West in the throes of economic and social development. In addition to the coins issued by independent states, there were also those from their colonies, providing a vast field of research for lovers of history and exoticism.

Our team of numismatic experts will advise you on buying and selling coins,

and give you advice on how to keep your collection in perfect condition.

Our addresses

Geneva: Rue François-Bellot 4,

CH-1206 Geneva

Dubai: 47-H Almas Tower

Jumeirah Lakes Tower